💬“Peace of the sort that brings wholeness, harmony, and health to our lives only happens when chaos, confusion, and conflict are included and transcended.”

- Harrison Owen, creator of Open Space Technology.

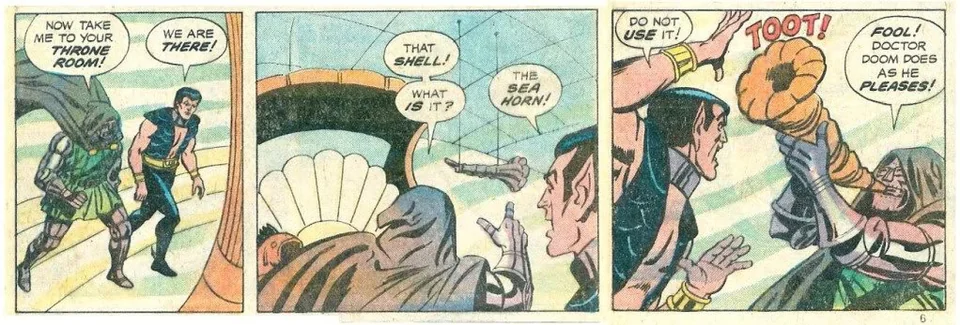

Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 3: Card. My daughter made this card for my birthday, to go with a themed collection of sci-fi novels.

#mbapr

📷 Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 2: Flowers. This extraordinary bunch came our way. What a beautiful gift!

#mbapr

📷Micro.blog photo challenge April 2024. Day 1: toy

How to set your own agenda

Harrison Owen, who died in March 2024, invented one of the most hopeful approaches to group facilitation I’ve ever come across. He called it ‘Open Space Technology’ (OST), but it was far from hi-tech. In fact, the main ‘technology’ was simply in how people in a group setting can interact fruitfully with one another, even when they really don’t agree.

“Peace of the sort that brings wholeness, harmony, and health to our lives only happens when chaos, confusion, and conflict are included and transcended.”

- Harrison Owen, creator of Open Space Technology.

I first came across Open Space as a means of organising workshops in highly contested political spaces.

In the UK during the 1980s and early 1990s progressive social activity was constantly undermined by Trotskyites (or whatever they were) striving to co-opt social movements for their own ends. There was always a risk that as soon as you set up a committee of any kind, they’d get themselves voted onto it and turn it into a front for the true workers revolutionary communist workers party, or some such combination of those terms.

But what were the alternatives? The Labour Party had been hammered with this problem, and had settled on a full-blown witch hunt against anyone affiliated with the Militant Tendency, which like a monstrous baby cuckoo had nearly pushed them out of their own nest. We’d witnessed how the so-called cure was nearly as bad as the disease.

I think it was about 1992 when we organised our own small Open Space event. Of course, the entryists turned up, but the Law of Two Feet really stumped them. When they realised anyone could set the agenda they were delighted. This must have seemed much easier than having to take over by stealth! But when the discussions began they were confounded by the fact that, equally, anyone could just walk away and find something more important to them. To everyone except the entryists, the experience was delightful.

Image by Chris Kinkel from Pixabay

Of course, OST didn’t change the whole world, and it’s not useful for every meeting. But it was formative for me personally, because I could see how people could come together to identify, commit to and begin to solve their own problems, without waiting for someone else to do it for them.

Open Space Technology has also left a strong mark on facilitation generally. Unconferences, World Café, Bar Camp, the Art of Hosting, design sprints, and many other approaches owe a great deal to Harrison Owen’s pioneering determination to trust people to pursue their own agendas.

Vale Harrison Owen.

More:

Working in Open Space: A Guided Tour

Finished reading: A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers 📚

I found this almost too whimsical yet strangely moving. A bit like my life then.

When it comes to writing notes, how much mess is just enough?

Oliver Burkeman, author of Four Thousand Weeks, likes to keep his notes messy1:

“‘Messiness’, in this context at least, is just the state of not being so hubristic as to imagine that you know, in advance, precisely what’s required in order to do or to create something worthwhile. Which, of course, nobody does.” - The life-changing magic of not tidying up

I really appreciate the benefits of serendipity, but I also need some structure, which is why I’m happy with making atomic notes, densely linked. You might call it a Zettelkasten. Burkeman says he tried a Zettelkasten approach to his notes, but found it too organised.

That’s not at all how I’ve experienced it.

The image that for me best sums up this process of making short notes to create longer pieces of writing is that of my little worm farm. All sorts of scraps get dumped in at the top. And mostly unseen, the worms turn everything into nourishing compost.

It’s almost magical.

So instead of being obsessive, I just have a few simple rules that I mostly stick to.

- Plain text (Markdown) notes.

- Each note is a single idea with a unique ID.

- Each note deserves a clear title.

- Notes link meaningfully to other notes.

And while this little system might not result in much tidiness, it’s still really neat.

Really looking forward to forward to photoblogging in April. It’s simple: just post a photo every day for a month. But I’ve been surprised to find how much I like it. Thanks to @jean, who has some thoughts on whether or not it’s a ’challenge’.

Don't make a Zitatsalat out of your writing

Zitatsalat? What does that even mean?

Yes, Zitatsalat. I found this lovely but rarely used German term in the title of a book by the journalist Stephan Maus. The book’s name is Zitatsalat von Hinz & Kunz.1

I love the rhyming rhythm of this compound term, but what does Zitatsalat actually mean?

Well, Zitatsalat translates as Quote Salad. It’s not a compliment.

Zitatsalat, by Stephan Maus (2002).

What’s wrong with quoting other writers?

There’s a temptation for those writing by means of a Zettelkasten, or card index, to use too many quotes in their writing - to collect a whole garden of notes, then serve them all up on a large plate of mixed leaves. Perhaps this is because the Zettelkasten approach to making notes makes it almost too easy to dish up a pretty indigestible salad of citations.

The subtitle of Maus’s book is: ‘Handpicked from the Zettelkasten’, and it’s true, the Zettelkasten makes it easy to gather and rearrange the pithy quotations of other writers.

But that doesn’t mean you have to use them all in your own writing. It’s fine to collect interesting quotations and excerpts from books and videos and articles and podcasts. But on their own they don’t belong to you, and you can’t just string together a pile of quotes and call it an article. It’s important to reflect on your reading and make it your own. That means writing about what the wise words of others mean to you, because:

Nothing says “I didn’t think this though for myself” like a direct quote.

Sure, it’s a salad, but is it your salad?

Write memos about the quotes you collect

One way of treating the process of gathering quotes from your reading is to see it as being a bit like the grounded theory process of gathering and reflecting on interviews. In this process the researcher records an interview, using direct transcription, but also reflects on the interviewee’s words by means of writing memos.

You don’t just write down the words of others. As you progress, you also write your own reflections on what the others have said. Then, when it comes to writing a longer article or book, the memos serve as important raw material.

The Wikipedia entry on grounded theory says:

“Memoing is the process by which a researcher writes running notes bearing on each of the concepts being identified… Memos are field notes about the concepts and insights that emerge from the observations.”

But I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking it’s really not cool to quote, and especially not Wikipedia.

And you’re right.

Chili, Tropea, Calabria, Italy. Norbert Nagel / Wikimedia Commons. License: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Don’t plate up a meal that can’t be eaten

I’m as guilty as anyone of trying to pack in as many quotes as possible in my writing.

The APA Style Guidelines say it’s usually better to paraphrase rather than to quote directly2, but did I listen? No!

When I studied psychology I found it almost impossible to follow the very clear assignment instructions not to include any direct quotes at all.

Because I love quotes!

And, truth be told, I love quote salad, it’s delicious.

But even I have to admit it can get pretty indigestible really quickly.

Years ago, when we lived in the West of Scotland we enjoyed the Calabrian chili pasta served by our local Italian restaurant, and as we began making it at home, we grew accustomed to the tremendously hot chilies we were using. Then one evening we served our favourite dish to some unsuspecting visitors. Too late we realised our mistake. They were completely unused to this kind of heat. I remember watching in dismay as they sat quietly but in obvious distress, as though expecting smoke and flame to erupt from the top of their heads like a volcano. We were so apologetic, but it was too late.

Zitatsalat is a strong dish. So by all means, offer your guests some quotes.

Just not too many.

Very few, even.

So for now, here are as few quotes as I can manage:

- Christian Tietze: You need to stop relying on a source and have faith in your own thoughts.

- Bob Doto: Your zettelkasten should be made up of your ideas about the author’s ideas.

- Andy Matuschak: Collecting material feels more useful than it usually is.

- and a reference, just because I can’t help myself: Chametzky, Barry. 2023. “Writing Memos: A Vital Classic Grounded Theory Task”. European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 3 (1):39-43. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejsocial.2023.3.1.377.

Hugo shortcodes in micro.blog

Here’s a quick test of Hugo shortcodes. I’ve been reading some tips for making the most of the Hugo web rendering system.

But it turns out I can’t use those ‘box-tip’ shortcodes in micro.blog

More research needed…

Perhaps I can just do the same thing with HTML and styling.

Info! Yes, here’s a basic information box.

…well so much for the styling!

🌊 A blissful Autumn weekend swimming and surfing #pacificwavewednesday

Surf Beach at Kiama, New South Wales

Work as if writing is the only thing that matters

“Work as if writing is the only thing that matters. Having a clear, tangible purpose when you consume information completely changes the way you engage with it. You’ll be more focused, more curious, more rigorous, and more demanding. You won’t waste time writing down every detail, trying to make a perfect record of everything that was said. Instead, you’ll try to learn the basics as efficiently as possible so you can get to the point where open questions arise, as these are the only questions worth writing about. Almost every aspect of your life will change when you live as if you are working toward publication. You’ll read differently, becoming more focused on the parts most relevant to the argument you’re building. You’ll ask sharper questions, no longer satisfied with vague explanations or leaps in logic. You’ll naturally seek venues to present your work, since the feedback you receive will propel your thinking forward like nothing else. You’ll begin to act more deliberately, thinking several steps beyond what you’re reading to consider its implications and potential.”

- Tiago Forte’s summary of How to Take Smart Notes, by Sönke Ahrens

The card index system is ‘a thing alive’ - or is it?

Niklas Luhmann, the famed sociologist of Bielefeld, Germany, wrote of how he saw his voluminous working notes (his ‘Zettelkasten’) as a kind of conversation partner, which surprised him from time to time. But he wasn’t the first to suggest that a person’s notes might be in some sense alive.

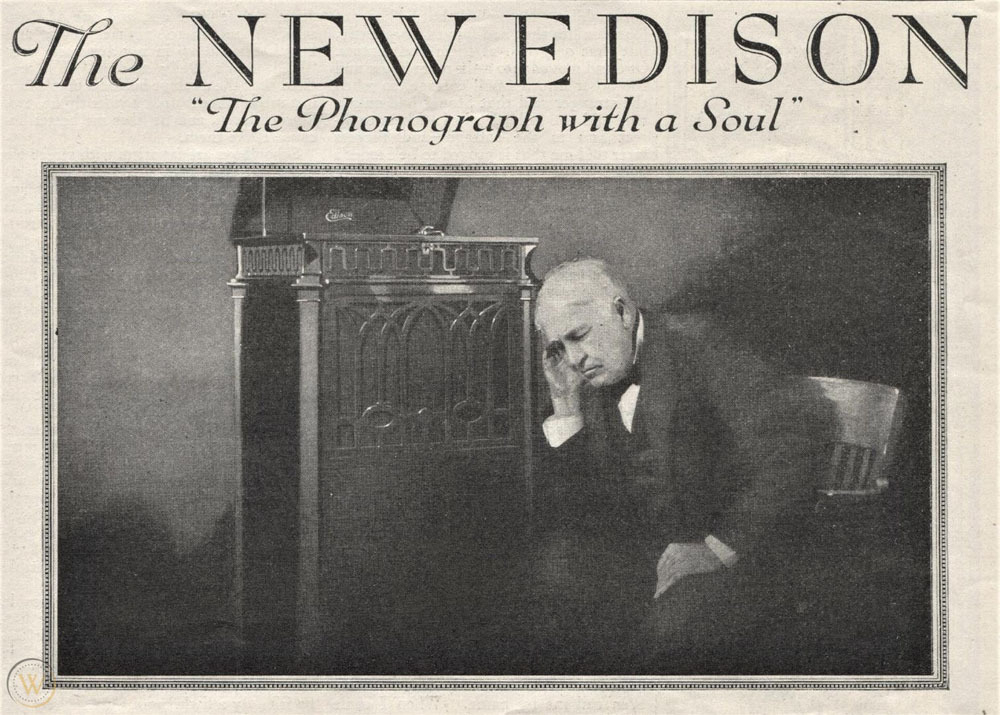

At the end of the Nineteenth century there was a massive explosion of technological change which affected almost every aspect of society. People marveled at new invention after new invention and there was a tendency to see mechanical and especially electrical advances as somehow endowed with life. The phonograph, for example, was held to be alive and print adverts even claimed it had a soul.

Huge industrial transformation led to fundamental changes in business administration. Yet again, information threatened to overwhelm with its sheer quantity. The index card system was adapted for new circumstances, and it too was seen as somehow alive. Manuals, sometimes sponsored by office furniture manufacturers, explained how to operate this new system.

One such manual, Julius Kaiser’s The Card System at the Office (1908) emphasised the central role the humble index card now took:

“The set of cards can fairly be regarded as the basis of the entire system, hence it is properly called the card system.” (para 59 Definition)

Another example of these ‘card system’ manuals is R.B. Byles’s The card index system; its principles, uses, operation, and component parts (1911).

This short volume begins memorably:

”Roughly speaking, the world is divided into two classes : those who use the Card Index System and those who do not.” (p.v)

The first chapter introduces the metaphor of the card system as a living entity:

“an alphabetic file is a dead, inanimate thing, giving forth only such information as it is compelled… A file based on the card index system is, on the other hand, a satisfactory and economical system of dealing with every sort of material, and is moreover a thing alive, ready at all times to place at the disposal of those who consult it all that information which in the past was regarded as the special attribute of the man [sic] of long experience.” (p.8)

As we approach the second quarter of the Twenty-first Century, the tendency to believe our new technology is somehow alive re-appears. Large language models talk back to us with eery proficiency. But just as the phonograph and the card index obviously aren’t alive, we’ll look back on this period and recognise quite clearly that our latest AI tools aren’t actually alive either. Metaphors can be useful, provided we don’t forget that they’re just figures of speech.

This being the case, it’s time to celebrate those who are really living: us, the people who animate the otherwise inanimate technologies of every era.

Three ways my notes might be ‘alive’

Nevertheless, there are at least three directions in which it might still be reasonable to think of your collection of notes as being alive.

The first direction is towards the idea of the ‘extended mind’, which I wrote about in How to make the most of surprising yourself.

You could view your collection of linked notes as part of your extended mind, which your brain creates constantly by co-opting its wider environment into its own processing activity. Brain and environment together create mind. On this account I might view ‘aliveness’ as a quality that arises at the intersection of myself and my world, and therefore out of the interaction between myself and my notes.

In her book, The Extended Mind, Annie Murphy Paul says:

“We extend beyond our limits, not by revving our brains like a machine or bulking them up like a muscle — but by strewing our world with rich materials, and by weaving them into our thoughts.”

The second way of thinking about this is a kind of formalisation of the idea that aliveness happens between people and their world. One such formalisation is known as Actor Network Theory. This concept claims that everything that exists, happens in complex networks of relationships.

Perhaps these early encounters with ‘living’ technology that I described earlier were grasping after a perception only later addressed systematically by intellectual developments such as Actor Network Theory, which proposes that non-human entities do have agency in the ‘parliament of things’.

Bruno Latour, the sociologist most strongly associated with ANT, said he’d have preferred to call it ‘actant-rhizome ontology’ if that had sounded better (sorry Bruno, it really didn’t). I wrote a little about this when I claimed a network of notes is a rhizome not a tree.

The third way of thinking of my notes as being alive in some sense relates to Lynne Kelly’s work on memory. I referred to this in The mastery of knowledge is an illusion. My thinking here was strongly influenced by the wonderful book Kelly co-wrote with Margo Neale: Songlines: the power and the promise.

Non-literate, oral cultures live in an enchanted world, not necessarily in a magical sense, but in the sense that the whole environment ‘speaks’, as part of a wider extended mind. Geographical features are not merely ‘dead matter’. They’re alive to tell stories which recount histories and genealogies, to give blessings and warnings. Plants and animals are similarly endowed with a depth of meaning. This is the world that literate culture has exiled itself from, but could perhaps regain.

So, are my notes ‘a thing alive’? Well, not exactly - but then not exactly not, either. Perhaps in time this is how we’ll come to see AI too, as existing in a kind of liminal space somewhere between living and non-living.

Whatever the conclusion, I’ve found this a useful question to think with.

See also: Jules Verne could have told us AI is not a real person

References

Byles, R. B., 1911. The card index system; its principles, uses, operation, and component parts (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons) view online.

Kaiser, Julius, 1908. The Card System at the Office (London: Vacher and Sons) view online

Margo Neale and Lynne Kelly, 2020. Songlines: The Power and Promise. Thames and Hudson.

Annie Murphy Paul, 2021. The Extended Mind. The power of thinking outside the brain. HarperCollins.

Sayes, Edwin, 2014. “Actor–Network Theory and methodology: Just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency?.” Social studies of science 44, no. 1:134-149.

How to make Mastodon even more fun!

Here are a couple of fun websites that will make Mastodon (and possibly the whole fediverse) even more fun. I know, it hardly seems possible. And if you know of others, please let me know about them too.

Just my toots

Do you sometimes wish you could see all your posts on Mastodon in a long list with no distractions? Of course you do! Every day! That’s why justmytoots.com is here to help. And yes, it shows you just your toots.

For the record, I hate the word ‘toots’.

At least where I live no one thinks of flatulence when they hear it, but still, it somehow manages to sound even more stupid than ‘tweets’, which takes some doing.

Now, above the cacophony of all the tooting I can almost hear you ask, “What’s the alternative?” ‘Posts’, that’s the alternative, and that’s what I’m sticking with. Why not join me, world?

Until then, you can see just my toots at https://justmytoots.com/@writingslowly@aus.social

RSS is dead LOL

Now this one really is cool.

You know how everyone at the Internet always says ‘RSS is dead’, right? It’s so annoying!

But anyway, just type in a fediverse username into rss-is-dead.lol and up pops a list of RSS feeds for that user and every account that account follows.

Its amazing! Nearly everyone I follow has an RSS feed! Wow!

Pretty much proves RSS still ain’t dead. Take that, haters!

Bonus fact: it turns out you can use RSS to ‘boost your productivity’. I don’t know what that phrase means, but it sounds great!

Meanwhile, check out my graph, or whatever you call it, at rss-is-dead.lol.

💬 “The real issue with speed is not just how fast can you go, but where are you going so fast? It doesn’t help to arrive quickly if you wind up in the wrong place.” - Walter Murch, In The Blink of an Eye.

Found at Austin Kleon’s post, Hurry Slowly

How to start a Zettelkasten from your existing deep experience

An organized collection of notes (a Zettelkasten) can help you make sense of your existing knowledge, and then make better use of it. Make your notes personal and make them relevant. Resist the urge to make them exhaustive.

Don’t build a magnificent but useless encyclopaedia

I guess we all start from our existing knowledge, since none of us is a blank slate. You could just start with what most matters to you right now, and work from there. That’s because it’s more useful and feasible for your system of notes to be personally relevant than to be generally encyclopaedic.

There’s a big difference between an encyclopaedia and a human brain.

- The encyclopaedia has the information but no effective way of showing what actually matters at the moment.

- The brain is the opposite: it knows what matters right now but can’t remember all the details.

Document your journey through the deep forest

The Zettelkasten is a useful middle way between these two extremes. It’s a tool to help you make and maintain personally useful trails through the deep forest of accumulated knowledge. Because these trails are useful to you, the expert, they are very likely to be helpful to someone coming up behind you.

On this basis I think there’s no point in trying to recreate, say, ‘20 years of project experience’ in a Zettelkasten. That would be like building your own Wikipedia. It would be a beautiful construction but how would you use it, and would you really be creating knowledge you couldn’t find elsewhere? (Maybe this really is what you’d like, though, I don’t know).

Avoid inert ideas

On Reddit u/cratermoon pointed me to Alfred North Whitehead’s classic essay about “inert ideas” PDF. According to the philosopher and educationalist, there is a great difference between what you remember and can repeat, and what you can actually apply.

“ ‘inert ideas’ – that is to say, ideas that are merely received into the mind without being utilised, or tested, or thrown into fresh combinations.”

The Zettelkasten method is at the very least a means of throwing your ideas into fresh combinations, to see what’s useful and what’s merely received knowledge.

Converse about what really matters to you

What the Zettelkasten excels at is systematising information that matters to you right now and that might matter in the future for a specific purpose. You have a bright idea in the present moment but your brain forgets it. Take a note, link it, and your Zettelkasten will resurface it for you. Your brain can probably remember this idea, given the right prompts, but the Zettelkasten is useful because it remembers the idea slight differently from how you do. Each idea in the Zettelkasten leads from and to different, and sometimes surprising places. In this sense your Zettelkasten is not so much a tool for remembering as a creative conversation partner about shared memories.

Imagine, then build, new knowledge products

Having said that, the Zettelkasten is also best when it’s aimed at the creation of products beyond itself. In other words, it’s primarily a working tool for creating new knowledge products. It’s really not just a reference catalogue or archive.

You might intend to create a book, or article series, or a course on project management, say, distilling your experience and passing it forwards. With that in mind, the Zettelkasten really is useful.

Where (and how) you go is more important than where you start from

The first note: the single most important thing. Here’s an example: “20 years of Project Management experience in two paragraphs”. Everything then follows as an extended commentary on that single idea. However, because it’s all connected, you don’t even need to start with the most important idea. You can just start with the first idea you think of right now. Where does it lead? The Zettelkasten process will take you there.

This unfolding process is the opposite of the standard practice. In the case of 20 years of PM experience the standard practice might be to take a conventional set of PM categories as your table of contents and then to write the same thing everyone else already wrote. The Zettelkasten method is specifically to deny the established categories and to allow the process to uncover new, better ones - new and unique trails through the forest of knowledge.

An example

This, for example, is how Niklas Luhmann worked. He was an experienced senior public administrator, with years of professional work behind him, before he became an academic, a professor of sociology at Bielefeld University. He used his Zettelkasten to break free of the established ways of understanding organisations, and to create an innovative theory of social systems, the subject of his many publications. Though he died in 1998, he was so prolific that there’s a backlog of books he authored. Two new volumes were published in 2021 1 and a collection of his lectures in 2022! The single idea that powered his Zettelkasten was: “Theory of society; duration: 30 years; costs: none.”

This article is adapted from a comment I originally posted on Reddit. There’s plenty more on this subject at Atomic Notes

💬"At what point does something become part of your mind, instead of just a convenient note taking device?"

A question discussed with philosopher David Chalmers, on the Philosophy Bites podcast.

🎙️Technophilosophy and the extended mind

So much of this depends on what ‘the mind’ means. Meanwhile, we do seamlessly interact with our note-making tools, to achieve more than we could without them.

Here’s how we journey beyond the ‘hero’s journey’.

Yes, we can be heroes, but does that mean we should be?

Yes really, we can be heroes. Thanks very much David Bowie! But if this sounds attractive, perhaps we should be careful what we wish for.

Do you want to be the hero of your own story? Perhaps you already are

According to reporting in Scientific American, imagining yourself as the hero of your own life gives you an increased sense of meaning.

“Our research reveals that the hero’s journey is not just for legends and superheroes. In a recent study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, we show that people who frame their own life as a hero’s journey find more meaning in it”.

But it’s not always great to be a hero

Meanwhile, from a quite different research perspective, comes a warning: Stanley and Kay (2023) caution that making people out to be heroic can inadvertently single them out for poor treatment from their peers.

“our studies show that heroization ultimately promotes worse treatment of the very groups that it is meant to venerate.”

Reading this I immediately thought of all those ‘heroic’ health workers who helped their communities through the COVID crisis at great personal cost and with very little long-term recognition (McAllister et al. 2020). In far too many cases, calling doctors, nurses and hospital workers heroes and even super-heroes ended up as quite tokenistic, little more than a way of justifying the exploitation of their labour. First they make you a hero, then they make you burn out.

Banksy’s artwork of a child playing with a nurse ‘superhero’ doll raised more than 16m for charity… but nurses' pay and conditions didn’t take off

Sometimes heroism isn’t what it seems

And here’s yet another, quite different warning: sometimes the person who sets themselves up as a classic hero is revealed to be anything but that. The case of Australian SAS fighter Ben Roberts-Smith is an extraordinary example of the moral jeopardy of a whole society desperate to believe in heroism. It seems this decorated and celebrated ‘war hero’ was really quite the opposite. The cover-up shows how much people want to believe in heroes, even when they don’t exist. This real-life tale has echoes of Beowulf to it. In Maria Dahvana Headley’s contemporary version (2021), the final words of that centuries-old tale ring painfully, bleakly, hollow with macho delusion:

”He rode hard! He stayed thirsty! He was the man! He was the man.”

So can we journey beyond the ‘hero’s journey’ already?

The hero’s journey trope has become so ubiquitous that it’s sometimes hard to remember that there’s any other kind of story. But there certainly is.

- Maureen Murdock (1990) and later Gail Carriger (2020) have both presented feminised versions of the heroic quest narrative. I’m not convinced that these heroine’s journeys are really all that different, though, since they still assume that heroism, albeit that of women, is where it’s at. At least there’s an attempt to re-balance the faulty idea that only men are at the centre.

- The New Yorker published a moving non-fiction account by Laura Secor of an Iranian woman’s bravery. The true story of journalist Asieh Amini doesn’t rely on a standard heroic arc, yet is highly effective. This is only one example of very many alternatives.

- Novelist Becky Chambers points out in a talk on YouTube that real life has no protagonists. Surely this can help us to question stale narrative forms, especially those which claim to be true to reality.

- Meanwhile, Christina de la Rocha is on a noble quest to put an end to the hero’s journey in literature and beyond. OK, not a quest. Perhaps she’d approve of Ursula le Guin’s claim that “the novel is a fundamentally unheroic kind of story”. More on that in a moment.

- Screenwriter Anthony Mullins has written a whole book showing that there’s plenty more than only one kind of character arc.

And author Jane Alison goes even further. In her book Meander, Spiral, Explode she notes that there are far more key patterns in literature than just the arc.

Not every story is a journey

Taking her cue from Joseph Frank’s book The idea of spatial form, and from Peter Stevens’s Patterns in Nature, Alison identifies some alternative or complimentary shapes.

I particularly like her concept of the story that meanders like a river, or ripples in waves and wavelets. These aquatic images remind me of something the former monk and psychotherapist Thomas Moore said about how life itself has a kind of liquidity to it:

“Your story is a kind of water, making fluid the brittle events of your life. A story liquefies you, prepares you for more subtle transformations. The tales that emerge from your dark night deconstruct your existence and put you again in the flowing, clear, and cool river of life.” (Moore, 2004, p. 61)

In his book on spatial form, Joseph Frank examines the structure of Djuna Barnes’s modernist novel, Nightwood. This novel doesn’t have a hero’s journey or a flowing river, but instead has a series of views or glimpses of life. He says:

“The eight chapters of Nightwood are like searchlights, probing the darkness each from a different direction, yet ultimately focusing on and illuminating the same entanglement of the human spirit . . . And these chapters are knit together, not by the progress of any action . . . but by the continual reference and cross-reference of images and symbols which must be referred to each other spatially throughout the time-act of reading.”

This searchlight metaphor is illuminating, but story structure can be yet looser, more diffuse than rivers and spotlights. I’m particularly taken with Ursula Le Guin’s carrier bag theory of fiction. Remember she said the novel is a fundamentally unheroic kind of story? If so then what is it?

“the natural, proper, fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag. A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.”

Le Guin’s insight is itself based on the carrier bag theory of human evolution, as described in Elizabeth Fisher’s Women’s Creation (1979).

“The first cultural device was probably a recipient …. Many theorizers feel that the earliest cultural inventions must have been a container to hold gathered products and some kind of sling or net carrier.” 1

Not everyone needs to be a hero to be a valid person. Mostly it’s better when we’re not. And not every story needs to be a hero’s journey for it to be worth the telling. The idea of the hero can be useful in some circumstances, dangerous in others. But more often it just gets in the way. Sometimes it’s really about “complex skills and compassion”. Sometimes it’s less about hunting and more about gathering.

So now, do you still want to be a hero, you hero you?

Now read:

More than ever, embracing your humanity is the way forward

References

Alison, Jane. 2019. Meander, Spiral, Explode. Design and Pattern in Narrative. New York: Catapult.

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. 1994. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years; Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. New York, NY: Norton.

Barnes, Djuna. 2006/1937. Nightwood, New York: New Directions.

Carriger, Gail. 2020. The Heroine’s Journey: For Writers, Readers, and Fans of Pop Culture. Gail Carriger LLC.

Fisher, Elizabeth. 1979. Woman’s Creation: Sexual Evolution and the Shaping of Society. 1st ed. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Frank, Joseph. 1991 The Idea of Spatial Form, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Headley, Maria Dahvana. 2021. Beowulf. A New Translation. Melbourne and London: Scribe.

Kaul, Aashish. 2014. Mapping space in fiction: Joseph Frank and the idea of spatial form. 3am Magazine

LeGuin, Kroeber, Ursula. 1989. “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” in Dancing at the Edge of the World. New York: Grove Atlantic Press. Accessed at stillmoving.org/resources…

Margaret McAllister, Donna Lee Brien & Sue Dean (2020) The problem with the superhero narrative during COVID-19, Contemporary Nurse, 56:3, 199-203, DOI: 10.1080/10376178.2020.1827964

Moore, Thomas. 2004. Dark Nights of the Soul. London, UK: Piatkus Books.

Mullins, Anthony. 2021. Beyond the Hero’s Journey: A Screenwriting Guide for When You’ve Got a Different Story to Tell. Sydney, N.S.W: NewSouth Publishing.

Murdock, M. 1990. The Heroine’s Journey. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Rogers, B. A., Chicas, H., Kelly, J. M., Kubin, E., Christian, M. S., Kachanoff, F. J., Berger, J., Puryear, C., McAdams, D. P., & Gray, K. 2023. Seeing your life story as a Hero’s Journey increases meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(4), 752–778. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000341

Secor, Laura. 2015. War of Words. New Yorker

Stanley, M. L., & Kay, A. C. 2023. The consequences of heroization for exploitation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000365

Stevens, P. 1974. Patterns in Nature, New York: Little, Brown & Co.

-

See also Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) on women’s role in technology, textiles and the string revolution. ↩︎